I’ve been raising chickens since about 2002. I grew up with chickens when I was really little, and it took me about 30 years to be able to get back to it. But with the exception of the year we moved from Colorado to Washington, I’ve kept chickens for the last 14 years. This was BEFORE the proliferation of back yard chicken raising blogs, websites and books. I bought a copy of Storey’s Guide to Raising Chickens, my husband built a coup (which was also a dog house/pen – they shared a dividing wall – which helped keep the chickens safe from predators but also safe from the dogs at night). I talked a bit about all of this here.

It’s really only been in the last few years that I’ve raised chickens with more of an eye to getting them to pay for themselves by selling the eggs. Here is a brain dump of factoids I’ve learned about raising chickens over the last 14 years, all in one place.

A chick, from the day of hatch to 10 weeks old, will eat 9 to 10 lbs of “chick starter”.

Older birds (over 10 weeks old) will eat around 1.5 lbs of feed a week.

Doing the math, to raise a bird to one year old, you need about 25 lbs of “starter” and 48 lbs of layer pellets. This cost me about $21 per bird last year, not including scratch and oyster shell, or any of the equipment (brooding lights, bedding, waterers etc.) to raise that bird. This is JUST to feed that bird. Not house it. Not give it bedding. Not fence it so it can run around on pasture. More on costs at the end of this post.

You need to feed your birds a balanced diet that has enough calcium in it. When I first started raising chickens, I bought scratch grains for their feed once I stopped feeding them chick starter. I had that image in my mind of the old time farm wife out in the chicken yard throwing “scratch” to the chickens from her apron. Pretty soon I had really thin egg shells and broken eggs. Layer feed is formulated to meet all of their nutritional needs. I prefer pellets to crumbles as I think there is less waste. Can you feed organic? Of course, if you can find the feed, and can afford it. Can you formulate your own, with the right mix of carbs and proteins and fats and minerals and vitamins? Absolutely, if you live somewhere that has access to the different types of grains you might need and storage and facilities to mix them. This PDF by Jeff Mattocks on how to formulate your own poultry blend has been in my files for several years. I would LOVE to make my own whole grain/legume blend. But for the size of my production, and lack of local availability of anything but 50 lb bags of grain (which is just ridiculous given that I live in “the bread basket of the west”) it just hasn’t been a huge priority for me. Joel Salatin’s books also have info on formulating your own feed mix.

Chickens are NOT vegetarians. When in the wild, they eat bugs, worms, and the occasional frog or salamander or even a mouse. So those egg cartons at the store that loudly proclaim “Veg Fed”. Yeah, whatever. Do I want my hens eating ground up other hens or other cast offs from the confined animal feeding operations. Oh hell no. But the idea that a chicken is a vegetarian by nature is just silly. While the commercial pellets I feed may not be perfect, I figure the hens are supplementing their diet with lots of other good healthy organic pasture stuff, and like eating a commercially grown french fry in a restaurant isn’t as good for me as a home grown organic one, given the balance of my diet, I think it’ll be OK.

Because my hens aren’t JUST eating laying pellets, but lots of other things that are diluting the calcium in the laying pellets, I also feed free choice oyster shell. It’s cheap and I go through about one 50 lb bag a year.

Most chickens will start laying eggs at between 16 and 24 weeks old. (That’s 112 to 168 days). Smaller birds generally start sooner, bigger birds later. Mine average around 5 months.

Chickens will lay where they want. Yes, there are certain things they look for – a fairly tight space that is dark/covered. But I’ve built a lot of nest boxes in the last 10+ years, and the one thing I’ve learned is that if your chicken is free-range and can find a hiddy hole, they will. We had a chicken who consistently laid on a wooden shelf in the barn for a while. Found a big pile under the platform/step up for the dog door. Under bushes. On top of feed bags. Sometimes you just find a random egg out in the yard, or on the floor of the hen house, and wonder what happened. Was a chicken just walking along and an egg fell out of their butt, lol? You CAN trim flight feathers (which doesn’t hurt them) so the don’t fly over fences (and yes, depending on the breed, they CAN fly for short distances. I had one do a good 20 ft across the yard the other day, over two sets of fences). And do your best to make where they are supposed to lay as attractive as possible, including fake wooden eggs so they get the right idea. But always be on the lookout for chickens in unexpected places, or the telltale cackle of “I laid an egg, I laid an egg” coming from over by the horse trailer rather than the chicken yard.

If you find a pile of old eggs, and you aren’t sure HOW old they are, put them in a bowl of water. If they lie flat on the bottom, they are still fresh enough to eat. Tipping up, I feed them to the dogs. Floating. Carefully throw them out. The air pocket in the egg gets larger and larger as the egg ages. Note: I never sell these eggs. Even the “fresh” ones. We just keep them for ourselves.

Chickens will typically lay almost an egg a day for their first year of laying. However, different breeds lay more than others. A breed said to lay 250 or more eggs per year is an excellent layer. One that lays 200 or more is a decent layer. Less than 200 a year and I figure, why bother.

Day length can affect laying. When the days are shorter than 12 hours (first day of Fall to the first day of Spring) some birds will stop laying all together, and most slow down a lot. (Because, lets face it, going back to the original purpose of laying an egg, which is to make another chicken – it makes no sense to raise your babies in the winter when its cold and there is not much around to eat), This slowing down is controlled by the chicken’s pineal gland, which stops producing the hormone that triggers egg laying when the days are shorter.

Supplemental lighting in the coop at night can keep your girls laying through the winter. But each bird only has so much egg potential over her life span. So keeping them laying “wears them out” sooner, as laying birds.

Chickens “molt” or lose and then grow new feathers, annually, with the first molt normally occurring at 16-18 months of age. It takes a lot of energy to grow new feathers, and a good amount of time (3 to 12 weeks depending on the breed and the quality of the feed they are getting). So if you get your chickens in March as day old chicks, they will go through their first molt 18 months later in the fall, and then every fall thereafter. Chickens don’t lay eggs when they are molting. It takes too much energy to both grow new feathers and grow an egg at the same time. Molting is also triggered by day length, and you can actually force a chicken to molt by manipulating it with artificial light, but that’s not something I’ve ever been interested in doing.

Some say birds on pasture lay fewer eggs. Laying pellet feed is formulated to be the birds sole source of nutrition, and the egg estimates for a breed are based on raising the birds in confined cages under controlled environmental conditions. Free ranging birds have a much more diverse and healthy diet, but not, perhaps, optimized for egg laying. The cold and wind and rain and snow and heat can all affect how many eggs are laid. Then again, some say with the right diet, pasturing can save on feed costs.

Regardless, pastured eggs are flat-out SO much better nutritionally and therefore, are SO very worth it, in my opinion. See this study by Mother Earth News.

Chickens can live for up to 5 years (much longer in some cases). They lay almost every day that first year. After the first year, they slow down to every other day or so, but lay larger eggs. After that they lay less and less often, and their egg shells tend to get thinner.

The best way to tell if a hen is laying is to look at her vent (the place where the egg comes out). If it is moist, and good sized (at least the size of a quarter), she’s laying. Also feel for her pelvic bones. If you can only get two fingers between them, she’s not laying. If you can get 3 or 4 fingers between them, then she likely is (the bones spread out to make room for the daily passage of the egg).

Newly laying birds lay smaller “pullet” eggs. Sometimes they lay huge eggs with double yolks. Sometimes they lay tiny “wind” eggs, with no yolk at all. Sometimes they lay an egg with just a membrane and no shell. Just like any teenager, it might take a month or two to get the hang of things, hormonally speaking. Then things tend to even out.

The lifespan of a fresh egg at room temperature is about a week. The lifespan of a refrigerated egg is 4 to 6 weeks. Eggs are coated as they come out of the chicken with a “bloom” that helps protect it from bacteria and other stuff. Get the egg wet, and you wash off the bloom. But sometimes you HAVE to get the egg wet to wash off poop and other dirt. If you are planning on incubating the eggs, it’s best to leave the bloom intact.

You can freeze unused egg whites (for those recipes that call for more yolks then whites) and then use them later to make Angel Food Cake. One whole large egg, out of the shell, is about 1/4 cup or 2 oz. About half of that is yolk.

Fresh eggs, when hard boiled, are almost impossible to peel. Save up a batch and let them age for a couple of weeks in the fridge and THEN boil them to make peeling easier. A dash of baking soda in the boiling water also helps.

Predators want to eat your girls. Coyotes, fox, hawks, owls, raccoons and possums (mostly after the eggs for the last two). The neighbor’s dog. The neighbor’s cat (or your own) for younger chicks. If you want your birds to free-range, know that you are taking a risk, and you might (likely) lose a bird or few. I’ve found headless hens on occasion (still warm – victims of a hawk – we butchered and ate the bird). We once had one of our dogs get into our hens when we were gone overnight (we still have the dog – against all odds, she’s never done it again). We had a fox get a few last winter. The best defense is well placed fencing and locking everyone up securely at night. Raccoons and other animals can dig UNDER fences. Sometimes an electric wire is the best option. Thankfully we don’t live in bear country. If you do, you ABSOLUTELY need to get electric fencing.

Sometimes birds just inexplicably die. You go out one morning and there is a dead, stiff bird laying on the floor of the coop. It happens. Because I often hatch new chicks from my own eggs, I always figure that while it is sad to find a dead bird, whatever the issue (egg bound – disease or parasites – or just old age) I don’t want those genetics in my flock, so I chock it up to better genetics and call it good. Knock on wood, I’ve NEVER had any issues with disease in my flock, bird flu or otherwise.

Raise young chicks on clean fresh bedding (I use bagged pine shavings from the feed store) separated from the ground (in a stock tank, and old plastic swimming pool, whatever) and start out with sterilized feeding and watering equipment and you won’t have problems with coccidiosis and won’t need to feed medicated feed to your chicks. It comes from contaminated soil. If the chicks aren’t in contact with the soil, they can’t get it. After a few weeks, I start to expose my chicks to greens and things by putting handfuls of grass into the brood tank. By 4 weeks I put them out on grass in a fenced “baby” pen on sunny days, slowly building up their immunity to whatever they might come into contact with. I’ve never lost a bird I’ve hatched myself to disease.

You don’t need a rooster for your hens to produce eggs, but you DO need a rooster if you ever want to hatch those eggs out into new chicks yourself (I bought 10 Rhode Island Reds last spring at $3.10 each because I wanted to add some non-broody egg layers to my flock. But if I’d hatched my own, that’s $31 in savings, right there). If you can deal with the crowing, roosters are also good defenders of their girls and worth having around in my opinion. (I kid you not, my husband grew up with a terrifying rooster who once managed to kill a coyote). I try to maintain a 10 to 15 hens to one rooster ratio. I select for the least aggressive males. Aggressive birds end up in the stew pot. Who’s the least aggressive? The one on the lowest rung/worst position on the roost when you go in at night and look. Also usually the one NOT participating in the gang rape of the hens when they reach about 6 months old. Yeah, that’s part of how I know its time to cull the roosters.

When you buy day old chicks at the feed store, they come in “straight run”, theoretically a 50/50 mix of male/female or “pullet” which theoretically are all female. I’ve often ended up with a surprise rooster in the pullet mix, and sometimes ended up with a skewed ratio from a straight run selection (some old timers know how to sex day old chicks, and will do this at the feed store when selecting their birds). I’ve always ended up VERY close to 50/50 when I’ve hatched out my own. There are some old wives tales about how to set your incubator temperature for more males or more females, but I’m not personally convinced biology works that way. Females have an ZW chromosome, males have a ZZ chromosome. (Like humans with XX and XY). Incubator temperature isn’t going to change which chromosomes you have.

When we butcher, since the birds generally aren’t that big or meaty and we don’t have a electric chicken plucker, we simply take the skin off of the legs/thighs and breast, then remove the legs/thighs, fillet off the breast, and call it good. Yes, a whole roast chicken is a beautiful thing. Yes, crispy rendered roasted chicken skin is yummy. Yes, you need to be a bit more careful not to dry out the meat when you are cooking skinless meat. But the time and mess it takes to scald, pluck and gut a chicken that doesn’t have that much meat on it, vs the time it takes to do what we do…well, there’s no contest. Haven’t plucked a chicken in 10 years.

Free range chicken meat, even if harvested before the birds are 6 months old, does NOT taste like store bought chicken. It’s darker, redder, more chewy, and just more “chickeny”. Just like the eggs from pastured birds aren’t the same as those from commercial producers from the store, birds that have actually been exercising and eating a diverse diet have meat that tastes different from those raised in huge confinement operations. Young birds are tender enough to eat like you would most chicken. Just expect to chew a bit more. Older birds (definitely if over a year) need to be pressure cooked to make them tender. But trust me, it will the the BEST chicken soup or dumplings you’ve ever eaten.

Reasons to keep chickens that have nothing to do with yummy eggs.

Pest control. We currently have 19 sheep and one goat. We have NO issue with biting flies, even at the height of summer, because the chickens run in the same pasture as the 4 legged animals, and scratch through their poop eating up any fly larvae that may be present. Grasshoppers? I see a few, but have never had a problem with them. Slug issues? Almost nonexistent with chickens and ducks (and they were BAD when we first got here).

Compost. We practice a deep bedding technique, where we add dry bedding (think carbon) to the floor of the coop (think nitrogen from the poop) on a regular basis. Joel Salatin says, if you can smell the manure, add more carbon. About once a year, we clean out the whole coop and make a large pile of chicken poop compost, watering the layers as we go. Within a few days, it’s heated up and steaming. We cold compost it (ie let it sit and don’t turn it) for a full year. Then we use this lovely composted manure on the fruit trees and in the garden. Don’t ever use chicken manure fresh. It’s really high in nitrogen and will burn your plants.

Soil turnover/aeration. Lets face it, chickens are just much smaller versions of dinosaurs, with those great big scratching Godzilla feet. Don’t ever let them into your garden early in the season. They will dig up all of your seedlings and eat all of your worms. But their constant scratching, looking for seeds and insects in the pasture, is great for keeping things stirred up and moving through the system.

Food NEVER goes to waste. Left over rice? Winter squash you didn’t get to starting to turn in the pantry? Salad greens starting to go off? Skins and peels from canning tomatoes? Squishy overripe apricots? Chickens to the rescue. We have a lot of walking composters on this farm, including rabbits and a goat who will eat most anything. But I DO love boiling up an old squash and watching the chickens work their way through the steaming pile in about 5 minutes.

Thinks go consider when choosing a breed.

- Egg color – there is NO difference nutritionally between white and brown eggs, but to me, brown eggs scream “farm” and so I choose brown egg layers. You can generally tell the egg color by the chicken’s “ear” feathers. White = white eggs. Other colors = brown eggs. Cheek tufts = easter egger chickens = colored eggs.

- Egg production – I look for 200 or more eggs per year.

- Temperament. Flighty high-strung birds are a pain in the butt when you have to collect eggs out from underneath them or trim flight feathers or cull the flock. Calm birds are just SO much more pleasant to be around. But there’s a lot to be said for alert too. Alert birds on pasture are better at noticing a hawk overhead and taking cover. I’ve had buff orpingtons off and on for years, but recently decided there is such a thing as too calm.

- Tendency to go broody. Yes, there is something very “natural” and sweet about seeing a mama hen sitting on a clutch of eggs, not hardly eating or drinking (or pooping) for 3 weeks. And letting her raise her own chicks takes the work off of you to keep them warm and fed for their first 6 weeks of life. But…there are problems. Other hens will sneak eggs into the nest, and so you end up with a bunch of different aged eggs in there (mark the eggs and remove any new ones daily). It also takes a nesting spot out of production, which may not be what you want if you are short on nest boxes. Once hatched, feeding mama and babies needs to happen AWAY from everyone else. They need different food (mama can eat the same chick starter as the babies – she doesn’t need the extra calcium in the laying mash at this time anyway) and a separate location so the little ones don’t get lost/stepped on in the mix of other hens.

Every time a hen goes broody, she stops producing eggs. I had 5 or 6 go broody last summer, REPEATEDLY, for more than 3 weeks at a time, even though I was removing their eggs daily. Every day she doesn’t lay an egg is less $ in your pocket. So, while having one broody hen is fun, having a breed that tends to go broody is a pain in the ass.

By the way, two methods to break a broody hen out of her broodiness. 1) Remove her to a cage with a wire floor and no bedding. Give her food and water, but no place to nest. After 3 or 4 days, the brooding hormones will leave her body and she’ll go back into the flock. This DOES work. I’ve used it a couple of times. 2) Slip a frozen bottle of water under her. I’ve not tried this, but have heard that it also works.

If you ever want to move a broody hen to a new location, do it at night, gently moving her and the nest/eggs and preferably putting her in an enclosed space (large cage or dog kennel) so she gets back to the work at hand and doesn’t just wander off and start again somewhere else. Do as much of this as you can in the dark. - Egg layer, meat breed or dual purpose? Leghorns are known far and wide as one of the most productive egg layers ever, laying over 300 eggs a year. But if you’ve ever seen one, they are a skinny stringy bird. Most all of their physiology is dedicated to producing eggs, and that leaves very little left over for things like size and weight and breast meat. So, if you plan on butchering your birds on occasion, either as they get older, or to cull the roosters, it’s not a bad thing to keep dual purpose birds, so at least there is a bit of meat on the frame when you butcher them. Raising meat breeds is a whole other subject. One I won’t dive into today.

- Comb size/cold tolerance. If you live in a cold climate and are not planning on supplemental heat/light for your birds in the winter (which is a nice gesture, but really isn’t necessary, for the most part), hens (and roosters) with big combs will get frost bite on their combs. The tips will turn black, and they may lose parts of them. So, smaller combs are better for cold weather locations. Some birds also handle the cold much better. If you live in a cold climate, you want a well feathered, slightly heavier breed (surface to mass ratio, baby).

- Fancy breeds and/or bantams. Honestly, for me, I’m in it for egg production, first and foremost. Bantams lay little tiny eggs, and they tend to hide them in weird places. A lot of people love them. They aren’t my thing. Fancy breeds of chickens, like fancy breeds of dogs, just seem less practical to me. Plus, again, I’m in it for the egg production, not the feather plumage.

- Foraging ability. If a bird has been selected to live in a cage and crank out eggs, it’s probably lost a lot of its natural foraging instincts. Some breeds do better than others at finding their own snacks out in the yard. If you plan on pasture ranging your birds, look for breeds with known good foraging ability.

So, how the heck does anyone make any money raising chickens? Well, they are ruthless about maximizing production, culling non-productive birds, and charging a price for eggs/meat that covers their input costs, their time, and their overhead. Here’s a GREAT piece on how you should REALLY be pricing your eggs. I’d have to check the math here for my own farm. We raise turkeys and ducks as well, and all are out on pasture and a lot are heritage breeds, so its hard to know exactly how much each each bird is eating, and how efficiently that diet is getting converted into eggs and meat. There’s a reason the big egg production factories aren’t free ranging their birds. It’s not as efficient. I DO know I’m probably not charging enough. But at the same time, I always feel like farm fresh eggs are the gateway drug to all kinds of awareness of food quality, food sustainability, and buying local. I really want to make them an accessible and not an elitist product.

To maximize production (something I’m getting more serious about) and still practice a form of chicken husbandry that I feel benefits me, the farm, the chicken, as well as my customers, here is what I would/should be doing. Hatch out replacement hens every spring. Assume 50% of the hatch will be male, and most of those will be culled. Assume a few losses over the course of a year. So hatch enough to have a few extra. Each fall, cull the roosters from that spring, and all 2 1/2 old birds (ideally just as they stop laying and go into their second molt, which is about the time the NEW chicks from the current year start laying). Leg band or otherwise mark every other year’s birds, so that with the motley crew of hens that I can’t tell apart, I know who the older birds are. In the spring, when laying is in FULL swing (May for us) check all hens and cull any that are not laying. No point in feeding birds that aren’t earning their keep. I DO put a light in the coop in winter. I run it starting in late September, then turn it off mid November (before we butcher turkeys, in an effort to get the turkeys to stop laying eggs – and to give the ducks a break too). Then I turn it back on around the first of January, and it stays on until the first day of spring. You can use an inexpensive timer to turn it on and off so it doesn’t run all the time. Remember, they need 12 or more hours of “daylight” to keep laying. On our our shortest day of the year here in Walla Walla, we have 8 hours 38 minutes of daylight. This site will give you daylight hours for your location in a chart for the full year. Cool huh?

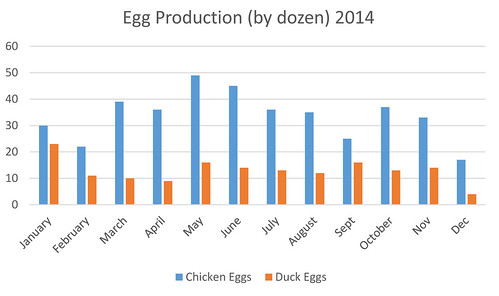

This is what my egg production cycle looked like this year, by dozen. That increase in October was the new birds coming on.

At this point, I’ve lost track of how old most of my birds are. I still have a few from my original flock, purchased back in early 2011, and I know the Welsummers and Cuckoo Maran’s that I added in the fall of 2013, and the Rhode Island Reds and Easter Eggers I added this spring. But the others that hatched this spring? And the ones hatched out in the spring of 2012 and 2013? Not a clue, lol. They are all mixed together. I have no idea who is laying. I have about 45 birds. I REALLY need to thin them out. Some of that will be happening this month (the very oldest birds first). Way too much feed going into birds that aren’t producing anything in return, as pretty as they are to look at. Generally, you want 70 to 75% of your birds to lay every day. I’m nowhere near that, but part of my goal for this year is to get a lot closer. It might take me a few years to get there.

Want to see how its REALLY done? Check out this Smith Meadows video on how they run 900 chickens free range. I highly recommend Forrest Pritchard’s book Gaining Ground!

Miles Away Farm Blog © 2015, where we really wish we had a mobile chicken processing unit available in this area. Sometimes it would be so much easier to just pay someone else to do the dirty work.

1 comment

Comments feed for this article

January 23, 2015 at 9:43 am

Kathryn Ann Moore

So fascinating …. Jennifer you are a major player in keeping a wonderful “lost art” alive. Our urbanized modern civilization has lost so much depth of knowledge of how the world really works. After Yellowstone explodes we may have to re-learn a lot of these old time arts. Such precious “wisdom from past generations” … so good to keep fresh.

Thanks for what you do !

Ann Moore (Camella’s Mom)